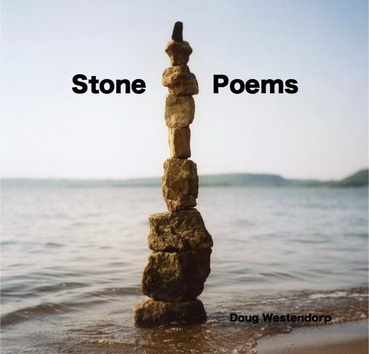

STONE POEMS (A BOOK)

I have self published a book of images of my rock stacking work, which I call, Stone Poems.

These images are of small, temporary still life sculptures, balanced rocks such as have been created in various cultures for thousands of years. I used stones found on location to create delicately arranged structures in the landscape. This book is of images from this series, paired with contemplative quotes. To see inside, and to order this book, please click on the cover image.

These images are of small, temporary still life sculptures, balanced rocks such as have been created in various cultures for thousands of years. I used stones found on location to create delicately arranged structures in the landscape. This book is of images from this series, paired with contemplative quotes. To see inside, and to order this book, please click on the cover image.

|

|

|

These "Stone Poems" are very simply formed. Each is composed of stones found on site, balanced freely. No adhesives or hidden props of any kind were used. Some toppled before I left the area, others stood for days. In each situation the landscape was essentially undisturbed. The photos were taken, but the stones were left.

I discovered this way of working in 1999, while playing with children in a Montana stream. As we all splashed around on the slippery stones, attempting our little towers, I was strongly drawn to the many possibilities which presented themselves in the contemplative vertical orientation of the arrangements. They echoed the gestures in the paintings I was doing at the time. In addition, I saw the stones had a unique relationship to the surrounding elements of earth, sky and water. They stood out or, more often, nearly disappeared, against the natural backdrop. Additionally, and most importantly perhaps, they seemed to have a surprising hallowing effect on the site, making the place feel, somehow, more holy.

There are no places on this earth that are not holy, of course, though sacrilege is a matter of course in our industrialized cultures. But people in all cultures across time have found the need to show particular respect for certain places. Interestingly, the shape of that respect is, universally, a vertical gesture. Whether a holy mountain, a ziggurat, or a tower, the steeple of a church or stupa, the human imperative seems to be for an axis or a pillar, connecting the earth to the heavens. It is called the "Pole of Heaven," the axis mundi, that which indicates that here is the center of the earth around which all mundane activity circulates.

This is an ancient gesture, an apparently archetypal imperative. Archeological evidence indicates that as far back as 11,000 BCE people were setting up stones in vertical arrangements in the Middle East. The ancient Hebrews called them masseboth, meaning, simply, "pillars." The most famous example, perhaps, is the story of Jacob in Genesis. As the scriptures relate, Jacob was traveling, alone and afraid, when he stopped to spend the night in the wilderness. He dreamed the dream we often call "Jacob's ladder," and when he awoke he called the place Beth-el, meaning, God is here. He then set up a massebah as a way of marking the place as holy ground.

I discovered this way of working in 1999, while playing with children in a Montana stream. As we all splashed around on the slippery stones, attempting our little towers, I was strongly drawn to the many possibilities which presented themselves in the contemplative vertical orientation of the arrangements. They echoed the gestures in the paintings I was doing at the time. In addition, I saw the stones had a unique relationship to the surrounding elements of earth, sky and water. They stood out or, more often, nearly disappeared, against the natural backdrop. Additionally, and most importantly perhaps, they seemed to have a surprising hallowing effect on the site, making the place feel, somehow, more holy.

There are no places on this earth that are not holy, of course, though sacrilege is a matter of course in our industrialized cultures. But people in all cultures across time have found the need to show particular respect for certain places. Interestingly, the shape of that respect is, universally, a vertical gesture. Whether a holy mountain, a ziggurat, or a tower, the steeple of a church or stupa, the human imperative seems to be for an axis or a pillar, connecting the earth to the heavens. It is called the "Pole of Heaven," the axis mundi, that which indicates that here is the center of the earth around which all mundane activity circulates.

This is an ancient gesture, an apparently archetypal imperative. Archeological evidence indicates that as far back as 11,000 BCE people were setting up stones in vertical arrangements in the Middle East. The ancient Hebrews called them masseboth, meaning, simply, "pillars." The most famous example, perhaps, is the story of Jacob in Genesis. As the scriptures relate, Jacob was traveling, alone and afraid, when he stopped to spend the night in the wilderness. He dreamed the dream we often call "Jacob's ladder," and when he awoke he called the place Beth-el, meaning, God is here. He then set up a massebah as a way of marking the place as holy ground.