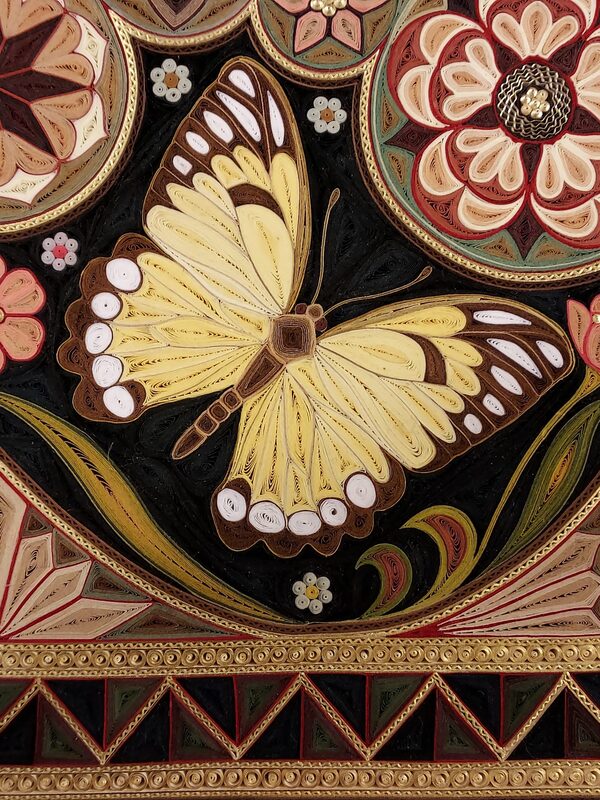

The Biomorphic World

When I was eight years old I memorized Psalm 24, which begins, “The earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof…” In my mind, the fact that the earth belongs to God was a given, what caught my attention was the additional fullness that also belongs to Him.

It is this fullness that draws my contemplative attention to this day. The earth is changing now, slowly and quickly. This earth, the biomorphic world, and the fullness thereof.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed